[dropcap size=big]S[/dropcap]ince the attempted coup d’état in July 2016, civil liberties and democratic values have been constantly curbed in Turkey.

The legitimate right of any democratically elected government to ensure its existence and to protect itself in case of illegitimate attacks on its institutions, has been over-exploited with the sole aim to silent all forms of internal dissent.

As highlighted by the recently published Amnesty International Annual Report, the overall human rights situation in the country is as critical as never before and no improvement is expected for the following months.

Although it is undeniable that the after-coup Turkey is experiencing an unstoppable downfall, a collapse from a democratic perspective, it would be way too simplicistic for any observer of the country’s domestic affairs, to not ponder and analyze, or rather criticize, the role and inaction of the external interlocutors while addressing the crackdown.

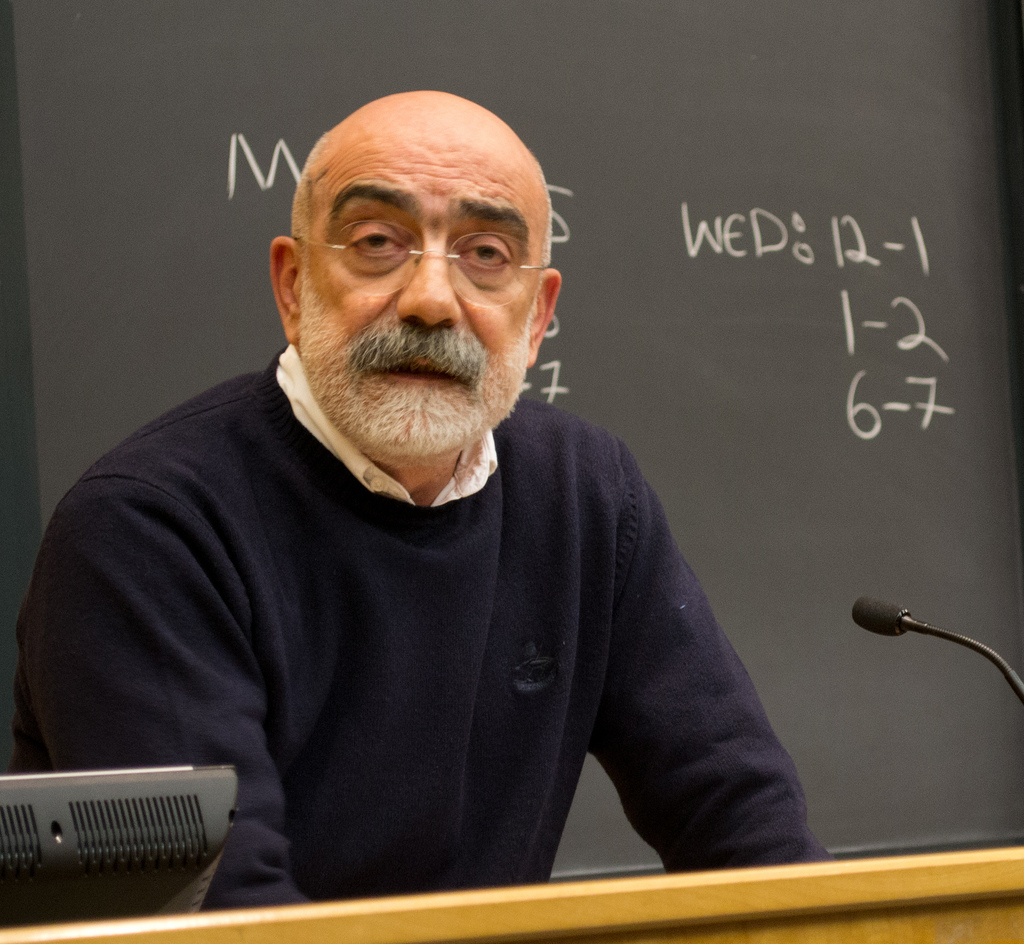

Several cases could be examined to investigate the erosion of the abovementioned fundamental rights but one among others significantly explains the current situation in Turkey: the ruling of 16th of February. In the broadly knownas the “Altans’ case”, involving the brothers Ahmet and Mehmet Altan, alongside the co-defendants Nazlı Ilıcak, Ahmet and Mehmet Altan, Fevzi Yazıcık, Şűkrű Tuğrul and Yakup Şimşek, all the media professionals were found guilty and given aggravated life sentences on charges of “trying to abolish the constitutional order of the Republic of Turkey by resorting to the use of force and violence” under article 309 of the Turkish penal code.

The verdict, the first one issued against journalists and intellectuals accused of being involved in the 2016 coup attempt, came one month after the ruling of the Turkish Constitutional Court’s (TCC) one which stated that the charges levelled against the Altan brothers were characterized by several irregularities. Despite the supreme court’s decision, a lower court decided to disregard the judgement and to continue the detention of the defendants.

The oddity of the verdict issued on 16th of February is its timing: on the same day, the Secretary General of the Council of Europe (CoE), Thorbjørn Jagland, was in Ankara delivering a key-note speech to over 400 over 400 candidate judges and prosecutors of the Justice Academy at the premises of the Constitutional Court, emphasizing the role and the importance of the Supreme Court in ensuring the values enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

Mr. Jagland, stressing on the CoE’s full support to Turkish authorities to investigate the attempted putsch, underlined as well the importance of the underogable rights such as the ones prescribed by art. 2 (right to life), art. 3 (prohibition of torture), art. 4 (prohibition of slavery and forced labour) and art. 7 (no punishment without law), expressing the European regarding the length and the scope of ongoing state of emergency. Emphasizing the crucial function of Freedom of Expression (FoE-art. 10 ECHR) and, consequently, of journalists and media outlets in contributing to the advancement of a healthy, democratic environment, the Secretary General cheered the activity of the TCC for upholding human rights, notably FoE and pre-trial detention (referring to the Mehmet Altan’s judgement, 11 January 2018), while in Istanbul the 26th Criminal Court was sentencing to life imprisonment six journalists, representatives of one of the pillars of a functioning democracy, as stated several times by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) as well.

The judgement of the Istanbul’s court shows the current erosion of the rule of law in Turkey, a process which is infringing the very foundation of the Republic and it is doing the groundwork for further violations of paramount rights, such as the right to a fair trial (art. 6 ECHR).

As remarked by Veysel Ok, co founder of the Media and Law Studies Association (MLSA) and lawyer of Deniz Yűcel and the Altan brothers, due to the refusal of a lower court to obey a Constitutional Court’s ruling, the only way for lawyers and inmates in Turkey is to address directly to the ECHR, despite not all domestic legal remedies have been exhausted.

The words of Mr. Ok shone a light on another controversial topic in regard to the current Turkish situation: the independence of judiciary, one of the most important checks in a democratic society. The disfunctioning of the judicial power, the interference of the executive power would continue to bring direct consequences in the country.

At this very moment, the ECtHR and European institutions should engage more to protect human rights values and fundamental rights as enshrined by the ECtHR, bearing in mind that there is no independency for rule of law in Turkey nowadays.

*Roberto Frifrini, currently based in Paris, is a human right defender focusing on

Turkey and South-East Mediterranean countries (minorities and migrants’

rights, civil liberties, geopolitics, EU policies) He is a member of the Human

Rights Agenda Association, a Turkish NGO currently based in Izmir and a

freelance journalist.