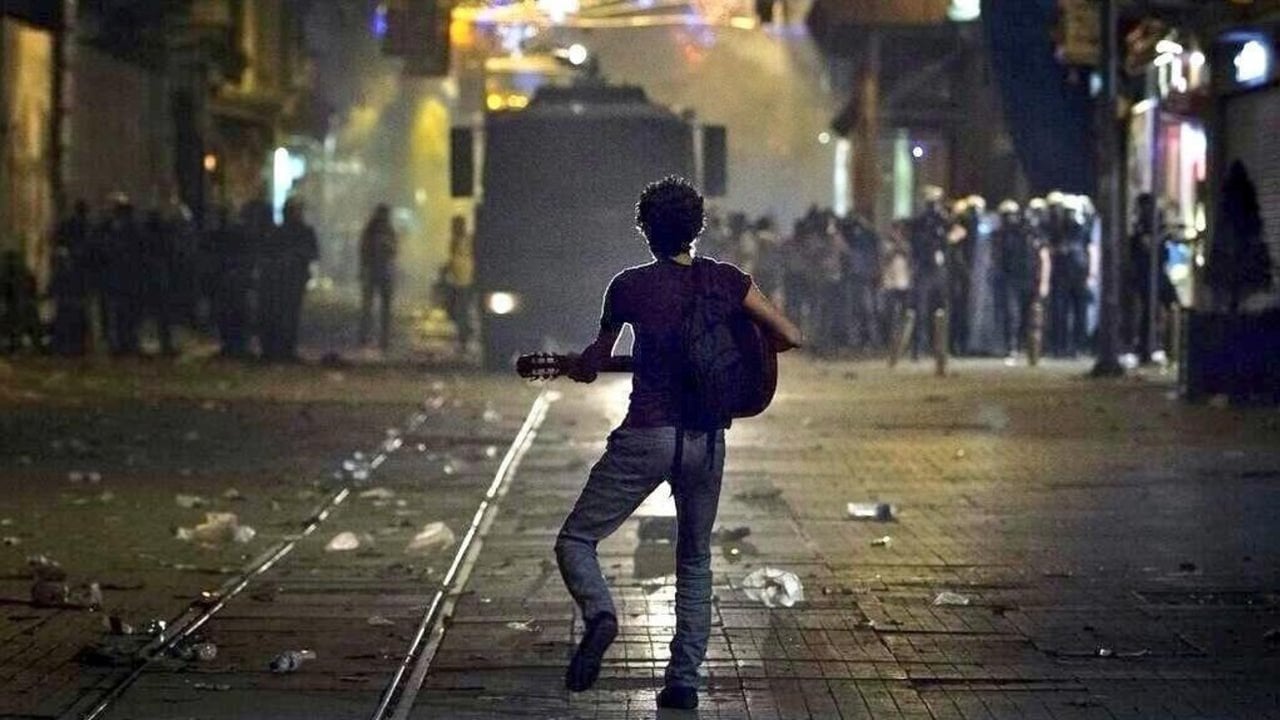

[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]n the late spring of 2013, Istanbul was aflame in an intoxicating, revolutionary atmosphere. What started as an environmentalist sit-in protest against the destruction of the last green space in Taksim Square for an Ottoman-theme shopping mall morphed into a nationwide, anti-government movement after Turkish police brutally attacked the small camp of protestors on May 30.

[authorbox authorid=”27″ ]

Within two days, hundreds of thousands of Turkish citizens, outraged by the footage of police brutality and the destruction of green space, marched into Taksim Square and other important public spaces across the country, forcing the police to retreat and beginning a weeks-long occupation of the square. At night, those who were unable to attend made noise with whatever kitchen utensils they had available in an act of solidarity. The success of the protests hinged on one fact alone; Turkey’s notoriously atomized opposition to AKP (Justice and Development) rule was able to unite.

Erdoğan’s hold on power never looked shakier than those two weeks in early June. For the duration that Taksim Square was occupied by protestors, the space became a microcosm of Turkish society itself. Nearly every facet of Turkish society was present and in solidarity; ardent secularists were seen marching beside Alevis and Sunni Islamists, Kurdish leftists fought the police alongside Turkish nationalists, and even the normally bitter rival fans of the Beşiktaş, Galatasaray, and Fenerbahçe football clubs united in opposition to Erdoğan.

No one was shunned – even normally invisible groups such as LGBTQ persons, physically disabled citizens, Armenians, and the Laz found their platform in Taksim Square. For minorities in a country with a strict monoethnic identity, the Gezi protests were a moment to share their culture with the rest of the country that had never quite existed before.

No one was shunned – even normally invisible groups such as LGBTQ persons, physically disabled citizens, Armenians, and the Laz found their platform in Taksim Square. For minorities in a country with a strict monoethnic identity, the Gezi protests were a moment to share their culture with the rest of the country that had never quite existed before.

This sharing of ideas is the most important lasting legacy of the Gezi movement. For many Turks, participation in the Gezi protests offered them their first meaningful interaction with minority groups. For participants from a CHP (People’s Republican Party)-voting background, the second largest voting bloc in the country, the Gezi park protests showed them that the traditional “enemies” they had been taught about – Kurds and Armenians – shared many of the same political goals.

Opposition politics would never be the same, and one of the products of the sharing of ideas at Gezi Park was the 2014 creation of the HDP (People’s Democratic Party), a minority coalition that also attracted a sizeable portion of normally CHP-voting Turkish leftists. The HDP was able to energize voters in a way that Turkey had rarely experienced before, resulting in the loss of AKP’s majority hold of the Turkish parliament in the June 2015, a loss that was not able to hold due to the refusal of the far-right MHP (Nationalist Action Party) to consider a coalition with Kurds and other minorities.

The protests sent a strong message to the AKP that their practice of endless land development and the selling off of public property had its limits. Erdoğan, taking a page out of Augusto Pinochet’s playbook, had sold his rule to the Turkish public by developing the weak infrastructure and rapidly expanding privatized real estate projects in the cities. While Turkey was in serious need of development, Erdoğan did not hesitate to wear out his welcome. Monolithic shopping malls sprang up across Turkey alongside mass produced, oversized Mosque projects at the expense of green space. The famously tree-lined Istiklal Avenue had its trees cut down to make way for more shoppers and storefronts. Istanbul’s northern forests, a unique future that no other major European city has, and one of the last remaining Laural forests in the world, quickly began to disappear. The environmental destruction became a visceral reminder of Erdoğan’s style of rule. It is no wonder that Turks were able to rally around an environmental movement to air the grievances.

It is not just within Turkey, but also outside that the Gezi protests had an immense effect. Erdoğan’s rule was heavily aided by an extremely positive international reputation, as Western Media and Al Jazeera published countless stories that gloated over Erdoğan’s “democratic-yet-Islamic” rule. (That such a thing should be so incredible to journalists displays a profound misunderstanding of the political history of the region as well as a deeply orientalist outlook). They fawned over what seemed like endless economic development and the lessening of political restrictions. Barack Obama even considered Erdoğan one of his best friends, and a man who he would consult for parenting tips (despite Erdoğan’s constant tirades against the freedom of young women).

While a closer look would have revealed the dark side of Erdoğan’s rule, the media and world’s political elite failed to do so, favoring the narrative of the unlikely hero that had realized how to mix Islam and Democracy. With the Gezi protests, images of appalling police brutality that resulted in 22 deaths and thousands of injuries and arrests were widely broadcast around the world. Erdoğan’s carte-blanche to govern free of criticism disappeared, and the world finally began to take a more careful look at his rule. We can assume Obama ceased to ask Erdoğan for parenting advice around this point.

While a closer look would have revealed the dark side of Erdoğan’s rule, the media and world’s political elite failed to do so, favoring the narrative of the unlikely hero that had realized how to mix Islam and Democracy. With the Gezi protests, images of appalling police brutality that resulted in 22 deaths and thousands of injuries and arrests were widely broadcast around the world. Erdoğan’s carte-blanche to govern free of criticism disappeared, and the world finally began to take a more careful look at his rule. We can assume Obama ceased to ask Erdoğan for parenting advice around this point.

Given what has happened since the Gezi protests; the collapse of the lira’s value, the dropping of democratic pretenses, the invasion of Afrin, Syria, the resumption of the conflict against the PKK, the shutting down of free media, the arrests of countless dissidents, and the alarming social restrictions that seem to be increasing at an exponential rate, it is easy to despair over Turkey’s future. As the five-year anniversary of the protests comes upon us, it is important to reflect on Gezi’s legacy. Erdoğan’s carefully cultivated image of boundless popularity and invincibility was shattered as the opposition united to deliver an unmistakable message that he would not be allowed to rule without resistance. Because of the protests, Gezi Park still exists today, and its shadow lingers menacingly over Erdoğan’s ambitions.

- Khashoggi , Journalism and Erdogan - 13/11/2018

- Turkey’s Christians Caught Between Trump and Erdoğan - 30/08/2018

- Istanbul Pride is too Big to Suppress - 16/07/2018