By YAVUZ BAYDAR

The return of Ergenekon as ultranationalists replace FETÖ

This was the headline of one of the most concise and interesting analysis I encountered lately.

The column was penned by my esteemed colleague Barçın Yinanç, with Hurriyet Daily News (an outlet affiliated with Doğan Medya Group, under fierce political pressure by the AKP, thus heavily self-censored) which stands out as a fresh and daring look into what takes place in Turkey’s ever-turbulent power struggle at the top.

Calling the spade a spade, and penetrating beyond the suffocating official narrative, it argued that the ‘inner state’ – what some call ‘deep state’ – had returned with full force, rising from a position of defeat – and back with a vengeance.

Here is how Yinanç described it, as she recapped the past 15 years, bringing us to her conclusions:

”When the Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power, the result took even its leadership by surprise. AKP leaders did not have the cadres to rule the country, as they were rather anti-establishment; they joined hands with the Gülenists.

In order to consolidate their stay in power, they realized they had to be accepted as a legitimate and workable partner by the West, especially the European Union.

While maintaining good relations with the EU, they realized that the bloc was critical of the state establishment in Turkey. In the eyes of the Europeans the military-judicial bloc was obstructing democratic reforms in the country. This bloc was against a democratic opening to solve the Kurdish issue, improvements in the rights of the country’s non-Muslim minorities and the full endorsement of fundamental freedoms like freedom of expression, while it was also blocking judicial reform.

In short, it was this blockage that was obstructing Turkey’s capacity to fulfill the democratic criteria that would open membership talks.

It was the same military-judicial bloc that had made life difficult for political Islam in Turkey. The Gülenists had suffered a lot from the wrath of this bloc, especially that of the military, which had blocked their penetration of the armed forces.

Turkey’s new ruling elites soon realized that EU reforms also meant the eradication of military influence from civilian life. So along with other reforms, steps to diminish the military’s role in civilian life began being put in force.

By 2007, the military’s arch enemies, the Gülenists, had succeeded in penetrating and fully exerting control over the judicial system and the police apparatus, but, in their eyes, the demilitarization of Turkish politics would not be wholly successful with some democratic reforms alone. As such, they pushed the button in 2007 for their huge vengeance operation, which came to be known as the Ergenekon trials.

The military-judicial bloc was a coalition of die-hard secularists/Kemalists and ultranationalists. The liberals and the democrats in the country had also suffered from that bloc and had long been suspicious of the bloc’s possible illegal activity. That’s why some endorsed these trials as a revolutionary step to finally demilitarize politics and consolidate real democracy.

But the Gülenists aimed solely at the secularist/Kemalist leg of the coalition, and it soon became clear that the legal case called Ergenekon, (the name given to the allegedly shadowy organization within the state) followed by the “Balyoz” (Sledgehammer) case, was a farce. They aimed at getting back at the soldiers and totally penetrating the army after the judiciary.

Liberal hopes that those with dirty hands within the state would be held accountable for past crimes were dashed.

After the breakup of the alliance between the AKP and the Gülenists, followed by the purges within the state, the ruling party needed to cultivate new cadres, especially among the security apparatus.

Guess who they opted for: the ultranationalists who are usually close to the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). For this group, the arch enemy is the liberals, democrats and left-wing intellectuals. Unable to cast aside its Cold War ideology, they are targeting the intellectuals, profiting from the dust created during the cleansing of the Gülenists.

A group that is loyal to a former interior minister who even served jail time is said to be very influential within the Interior Ministry and is believed to be behind the purge against the left-wing liberal intellectuals, who are losing their jobs even though they have no linkages to FETÖ.

The forces who blocked Turkey’s democratization process in the 1980s and 1990s are back again with their archaic mentality and are unfortunately proceeding full steam ahead in an effort to crush Turkey’s democrats.”

While disagreeing with some of her remarks, I find Yinanç’s final remarks as extraordinary: they are powerful in a sense that offers all the current and prospective analysis about the neverending power battle at Ankara’s top echelons fresh perspectives.

Let me explain on two points I disagree with Yinanç.

*It was not (what Yinanç calls) ‘new ruling elite’ who in the first place opened the gates of the security and judicial apparatus to Gülenists in the first place. It began, as a pattern, with the three-party coalition (DSP-ANAP-MHP) which preceded the AKP. Former PM Bülent Ecevit played a key role in the process; because it was his drive to launch reforms which later would pave way for membership talks with the EU. Ecevit was discontent with the human rights violations, which the continued military domination over politics had enhanced. He had contempt with torture, which during the 1990’s was systematic in Turkish police houses and prisons. He took the lead for an institutional reform within the interior an justice departments, and received large-scale assistance from some European countries in terms of education – seminars, courses and conferences. Appointments and recruitments in those structures played a big role, with mainly Gülenist elements in the front. This move, which later led to the abolishment of death penalty, caused a lot of dismay among the hardliners the military, police and judiciary; the ‘inner/deep state’ of Turkey felt the upcoming threat as an existential one. It must be a given that thanks to these new cadres – be them dominated by Gülenists – torture was devolved from the state of ‘systematic’ to ‘exceptional’.

*I am not at all sure that ‘Ergenekon’ and ‘Balyoz’ (Sledgehammer) cases were ‘farce’ – if ‘farce’ means a ‘sham trial’. There was more than enough in the core of both indictments that gave legitimacy to the implications against a limited number of officers at the very top in both cases, but it was soon politicized, made instrumental, and the team of prosecutors, be them some Gülenists and some not, blew the chances of a fair trial by being ‘used’ by the top executive political authority, Erdoğan, who had already declared himself as ‘chief prosecutor of the cases’. When the ground of the both cases were undermined, they paved way for another injustice, another collapse of the judicial structures, and paved way for all those who had to be tried robustly for being responsible for the past crimes such as coup plotting, and summary executions of the Kurdish opposition figures, to came back with a vengeance. So, it was neither independent liberal media nor the Gülenist grassroots who had to be blamed for the collapse, but some selected Gülenist and ‘arrivist’ judges and prosecutors and Erdoğan himself who pushed the wrong buttons which derailed Turkey’s democratization entirely.

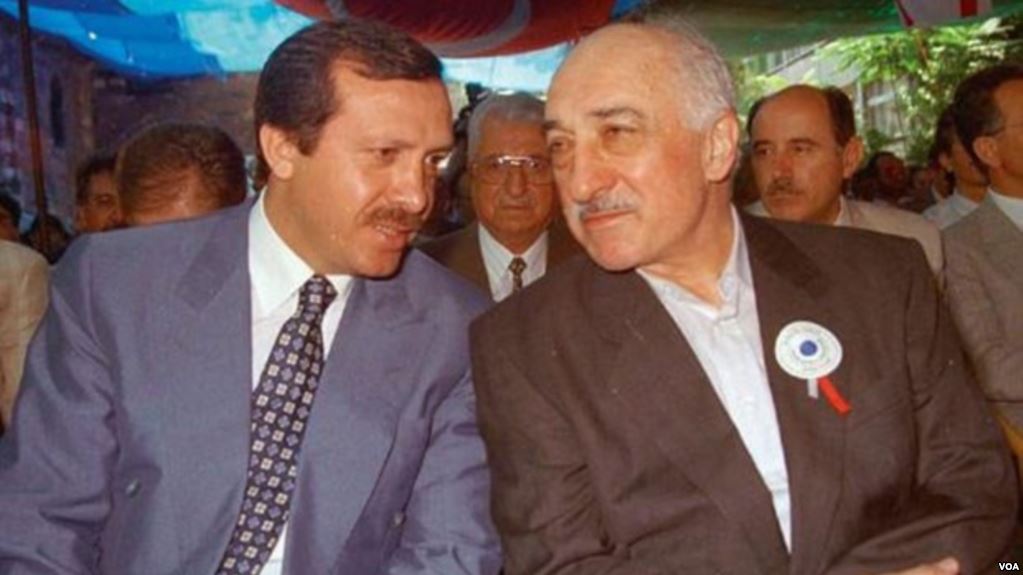

Recep Tayyib Erdogan (L) and Turkish cleric Gulen (R) next to each other during Erdogan’s mayorship in Istanbul

The final findings of Yinanç are, in my opinion, fully correct, and timely.

When Erdoğan and Gülen fell apart, beginning with Mavi Marmara incident, and with the closure of private tutorial schools (dershane), and an FBI-led graft probes landed like a bombshell, Erdoğan had to step back, rethink, and in sheer survival instinct, cut a new alliance with his foes of the past: the military and its ‘dark lackeys’ in the bureaucracy.

He knew that they had a common enemy in Gülen and his followers, a group that did not rank high at all in popularity amongst militarists, seculars, Kurds, Alevis, ultra-nationalists and leftists, and forged an alliance to declare them the only culprit. The military, who had long complained that Gülen was the enemy number #1 – shring the same position with Öcalan – agreed; redesigning a strategy that ‘new enemy of my enemy’ will do the dirty job, until it rose to regain the positions that it had lost.

The collapse of the Kurdish Peace Process, as well as the choreography and the aftermath of the ‘coup attempt’ fit perfectly into this picture, providing answers that the new alliance is keen on cleansing all that stand as potential alternatives to a power share, and in terms of a new social contract, democratisation.

Thus, ‘FETO’ was added as a new ‘master key’, to ‘divisive terror’ (attributed to the Kurdish Political Movement) to launch a project of a ‘monolithic Turkey’ where diversity, pluralism, dissent and civil society will be exterminated.

The AKP’s story stands as a spectacular case study in politics how a grassroots movement, elected massively to the power, starts well, and due to incompetence, ignorance, over-ambition and paranoia, refuses to share it; ending up with a personalization of it. A project that started with the hopes of building a democracy, turns in a slow motion to an autocracy.

(The article is originally published on VOCAL EUROPE on May 27, 2017.)