By LEVENT YILDIRIM

The unfolding of December 2013 corruption probes sparked off a renewed wave of undemocratic developments on the functioning and the independence of the Turkish judicial system. Following the disclosure of the probe in December 2013, which underlined the alleged role of the four ministers of the cabinet and the son of the then Prime Minister Mr. Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a number of worrying developments have been observed with respect to the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary.[1]

The storming legislative and institutional change forced by the executive in 2014 enhanced the perception that the judicial system is now controlled and changed by the state conveniently to serve its own purpose by means of amendments to the Turkish Criminal Code and Code of Criminal Procedure as well as the restructuring of the High Council of Judges and Prosecutors in 2014. The Turkish High Council Law No. 6087 was changed, which allowed more executive control over the functioning of the High Council of Judges and Prosecutors. The unconstitutionality of the bill was raised by all the opposition parties as well as by a great majority of lawyers and jurists.[2] The executive also succeeded in terminating the position of all the staff at the High Council through legislative action, which was normally a prerogative of the High Council.

The reshuffling of the Judicial Council on 15 January 2014 and the new appointments to the critical clerical positions following the mainly unconstitutional amendments of the High Council Law No. 6087, the Ministry and the executive inserted more control over the formation and functioning of the High Council. The Turkish judiciary had been systematically forged in the days up to the creation of the criminal peace judgeships.[3] The executive had already succeeded in taking extensive control of the judiciary mainly through a change in the formation and functioning of the High Council.

The criminal peace judgeships began their duties on 21 July 2014. The chronology of events and public statements made by Mr. Recep Tayyip Erdogan clearly evidence that the criminal peace judgeships had been created, structured, staffed and instructed by the executive specifically in order to fight against what Erdogan and his government called in those days the ‘parallel state structure’ allegedly linked to the Gulen group.[4]

The criminal peace judgeships were specifically created to take all the precautionary judicial measures necessitated by the existing and future investigations against the police officers and judges involved in the corruption investigations of December 2013 as well as to fight against the persons allegedly linked to the Gulen group. Thus, most of the allegedly committed crimes precedes the creation of the criminal peace judgeships which would raise the issue of violation of the principle of ‘natural judges’.

Defects and Anomalies of Criminal Peace Judgeships:

The creation of such special judgeships is incompatible with the principle of ‘natural judge’ enshrined under Article 37 of the Constitution, which provides that “no one shall be put to trial before a body other than the court he/she is legally subject to. No extra ordinary judicial bodies shall be established that would lead to putting a person to trial before a body other than the court he/she is legally subject to”. This provision prohibits the creation of courts with a competence to try cases relating to the events which took place before their creation. The legislature may of course have competence to reorganize the judicial system by setting up new courts and abolishing certain courts. Nevertheless, this should not be carried out with a view to violating the principle of ‘natural judge’. The creation of criminal peace judgeships sets a clear sample as to how a court or judgeship can be created with a specific political motivation and thus the principle of natural judge can be violated.

The principle of ‘natural judge’ guarantees that an individual may not be tried by a court or judgeship which was created before the crimes were allegedly committed and prohibits the establishment of a court specific to an event. There is ample evidence that the criminal peace judgeships were intentionally created against a specific societal section i.e. the so-called Gulen group. A judgeship devoid of the safeguard of the ‘natural judge’ cannot be considered as ‘a judge or other officer authorised by law’ under the provisions of Article 5(3) of the ECHR. The respective provision states that “Everyone arrested or detained in accordance with the provisions of paragraph 1 (c) of this Article shall be brought promptly before a judge or other officer authorised by law to exercise judicial power and shall be entitled to trial within a reasonable time or to release pending trial. Release may be conditioned by guarantees to appear for trial.” The creation of the criminal peace judgeships in order to try specifically the events that allegedly took place prior to its establishment violates the principle upheld by Article 5(3) of the ECHR.

International institutions believe that criminal peace judgeships are perceived as being close to the executive following the reshuffling of the judicial institutions after the December 2013 corruption investigations, and the politically motivated appointments and transfers of judges and prosecutors continued since then. The Amnesty International for instance observes that criminal peace judgeships with jurisdiction over the conduct of criminal investigations, such as pre-charge detention and pre-trial detention decisions, seizure of property and appeals against these decisions, came increasingly under government control.[5] The Venice Commission has more recently criticised the formation and functioning of the criminal peace judgeships and put forward a number of recommendations for its reform.[6]

The Constitutional Court had however dismissed on 14.01.2015 the constitutional challenge, stating that it cannot be alleged in objective terms that these judgeships are not impartial. The Constitutional Court had unanimously rejected the application for annulment of the establishment of criminal peace judgeships; and rejected by a majority the application for annulment of the procedure of appeal against the rulings of these judgeships.[7] Five members of the Constitutional Court were in fact of the opinion that the rules relating to the appeal procedure against the rulings of these judgeships violated the Constitution. The majority nevertheless applied a formalistic criterion over the constitutionality of the establishment of the criminal peace judgeships and did not find it necessary to question the substance of the claims in terms of the specific purpose of their creation, appointment process, functioning and flagrant cases of partiality.

The ‘criminal peace judgeships’ were given the sole authority for taking decisions in relation to the investigations and appeals against decisions, especially on issues concerning custody, arrests, property seizures and search warrants. These judges can decide on the launch of investigations (based on ‘reasonable suspicion’) and pre-trial detention (based on ‘strong suspicion’) for crimes that can be punished by at least two years of imprisonment. They combine the function of investigative judges and ‘judges of the liberties’, deciding on arrests, seizures, wiretaps and searches, pre-trial detention and release from pre-trial detention. The criminal peace judgeships basically take the most drastic measures up until the trial stage of a judicial prosecution, which depending on the case may last from one to two years or perhaps more. The executive intention for rushing to create these judgeships appears to take under immediate control of the investigation stage through the criminal peace judgeships.

The decisions of ‘criminal peace judgeships’ can only be appealed to another criminal peace judgeship, which raises question about fair process. Under the Code of Criminal Procedure, the decisions of a judgeship can only be appealed to the next number of judgeship that follows in row if there are more than one criminal peace judgeships and the decisions given by the last number of criminal peace judgeship will be appealed to the first number of the criminal peace judgeship in the same jurisdictional area. If there is only one criminal peace judgeship in a jurisdictional area, the decisions can be appealed to the judgeship sitting in the closest jurisdictional area. When an arrest and detention order is issued pending trial for instance by the 1. criminal peace judgeship, that decision can be appealed to the 2. criminal peace judgeship. If an objection to a detention order is refused for instance by the 3. criminal peace judgeship (assuming there are only three judgeships), that decision can be appealed to the 1. criminal peace judgeship. Thus, these courts clearly act as ‘closed circuit’ courts, which may be considered going back to the old ‘courts of special jurisdiction’ after Turkey abolished the problematic special courts in 2014.

Under the old rules of the Code of Criminal Procedure, the decisions of ‘criminal courts of peace’ during the pre-trial stage could be appealed to the ‘criminal court of first instance’ through an automated file distribution system in the court houses. As there was no specific assigned criminal court of first instance on duty for deciding on such appeals, an objection file could be distributed to any ‘criminal court of first instance’ available and even sometimes to assize courts in the courthouse to be allocated by an automated file allocation system. As no one could predict and direct which ‘criminal court of first instance’ would decide on the appeal, the courts would be relatively free in principle from any influence. This would mean that an appeal to a decision of a criminal court of peace could end up with as many as 50-60 judges in large courthouses, which would guarantee some degree of independence and impartiality of the judiciary.

Whilst, the decision of a ‘criminal court of peace’ was reviewed by a ‘criminal court of first instance’ standing higher in the hierarchy through the random distribution of files among so many courts, the new system of criminal peace judgeship allows the review of a criminal peace judgeships decision only by another criminal peace judgeship who are specifically appointed in limited numbers.

Article 19 of the Turkish Constitution and Article 5 of the ECHR contain parallel provisions in terms of their wordings, contents and purposes as regards ‘the right to liberty and security’. The said similarity also exists in relation to Article 19(8) of the Turkish Constitution and Article 5(4) of the ECHR. Article 19(8) of the Constitution reads as follows: “Persons whose liberties are restricted for any reason are entitled to apply to the competent judicial authority for speedy conclusion of proceedings regarding their situation and for their immediate release if the restriction imposed upon them is not lawful.” Article 5(4) of the ECHR provides that: “Everyone who is deprived of his liberty by arrest or detention shall be entitled to take proceedings by which the lawfulness of his detention shall be decided speedily by a court and his release ordered if the detention is not lawful.” The aim of both regulations is to provide the individuals detained with an effective legal remedy by which they can defend their freedoms, which may be accessible, allowing reasonable degree of success and creating the feeling of justice and thus preventing public authorities from arbitrarily restricting the right to liberty and security.

This aim will not be effectively realized when there are for instance two criminal peace judgeships, each of which is reviewing the other’s decisions. Each judgeship will be aware that it is controlling the decisions of the judgeship which will also review its own decisions in turn. This will create a vicious circle among the criminal peace judgeships which will consider the appeals of one another’s decisions. This closed-circuit appeal mechanism will result in the objection procedure becoming ‘ineffective and control in appearance’. This appeal system removes the possibility of effective control over the most serious intervention to the right to liberty and security such as arrest and detention, which should have been provided through assurances by a higher judicial authority. The previous system thus provided in principle the possibility of review of arrest and detention orders from ‘a different viewpoint by higher courts with a higher level of assurance’. The new functioning of the criminal peace judgeships further increases the problem of ‘internal institutional blindness’ when it operates as a closed-circuit appeal system. Thus, the close-circuit appeal system among the criminal peace judgeship is far from satisfying the legal guarantees enshrined under Article 19(8) of the Constitution and Article 5(4) of the ECHR.

Further, the decision given following an appeal to the criminal peace judgeship is final. An appeal to this decision must be normally reviewed by a higher court in the hierarchy of the court structure whenever this is available. Article 2(1) of Protocol No. 7 of the ECHR (Turkey is not yet a party) provides that anyone receiving a criminal punishment shall be entitled to request the review of his conviction or punishment by a higher court. It is also a universal principle of criminal law and an inherent nature of the appeal institution that the review of a conviction shall be undertaken by an impartial higher court in the structure of the court system. It cannot be argued that the same logic and the same characteristics deriving from the nature of review institution may not be valid for the appeal (objection) institution as a legal remedy. There are three criminal courts in the hierarchy of the criminal court structure under Turkish law situated at first instance level: criminal peace judgeships, criminal courts of first instance and assize courts. The legislative authority given by Article 142 of the Constitution in regulating the courts through acts of parliament cannot be taken to mean that the legislature can regulate this in any manner that it sees fit when there are higher courts in the system superior to the judgeships.

The independence and impartiality is the founding elements of a court or judgeship within the context of Article 5 of the ECHR (D.N. v. Switzerland; Nikolova v. Bulgaria, para. 49). An organ which is not independent and impartial may not be regarded as a court in the understanding of the ECtHR, even if it is named as such (Beaumartin v. France). The ECtHR, following its determination of a court as not independent and impartial, held that that court could not be considered as a court within the meaning of Article 5 and that the applicant’s custody period would not end by the decision of that court and thus Article 5(3) of the ECHR was violated (Assenov and Others v. Bulgaria, para. 148-149). According to the Court, appearing before a judge who is not independent and impartial will not be considered to ‘be brought promptly before a judge or other officer authorised by law to exercise judicial power’ and will not end the custody period and thus Article 5(3) of the ECHR is violated (Assenov and Others v. Bulgaria, para. 146-150, Nikolova v. Bulgaria, para. 51-52).

The ECtHR assesses the independence of the judiciary on the basis of three criteria: the manner and period of appointment of the members of the court, the availability of guarantees against external influences and the appearance of the independence of the court (Findlay v. UK, para. 73). One of the most important determinations of a court’s independence is the guarantee that the judges cannot be discharged from their existing duty without their request before the expiry of their terms, saved for appointment to a higher court (Campbell and Fell v. UK, para. 80; Lauko v. Slovakia, para. 63). There are scores of examples of the violation of this guarantee by the Turkish Judicial Council following its new formation especially following the government driven judicial election in October 2014. The intense circulation among the criminal peace judgeships is also another sign of arbitrary reassignment of the judges when they did not satisfy the executive with their decisions and ‘expected’ performance. The main reason behind the removals of these judges was that they either did not issue detention orders for some suspects or accepted some of the objections against the detentions and therefore released the suspects in investigations relating to the police officers.

Criminal Peace Judgeships under Emergency Regime

Following the mysterious abortive coup of July 2016, a wave of prosecutions was initiated by the government seemingly as a response to the failed coup. It has nevertheless quickly turned out that most of the prosecutions have nothing to do with the actual coup attempt but on the basis of allegations of membership, relationship or affiliation to the Gulen group (the government claims it to be a ‘terrorist’ group). The figures of dismissals, closures, seizures, prosecutions, arrests, bans etc. have greatly expanded since the failed coup and have now reached a tremendous scale, already undermining the state structure in the field of defence, security, judiciary, education and so on. The criminal peace judgeships have become all the more important and functional for the executive and its functionaries in the judiciary for the wave of massive arrests and other dramatic measures taking place in the chaotic circumstances following the attempted coup of 15 July 2016. The criticisms outlined above in relation to the structure and functioning of the criminal peace judgeship had a far too devastating impact not only due to the very high numbers of persons involved but also as a result of extraordinary powers given to the criminal peace judgeships and other judicial and non-judicial official bodies under the emergency decree laws.

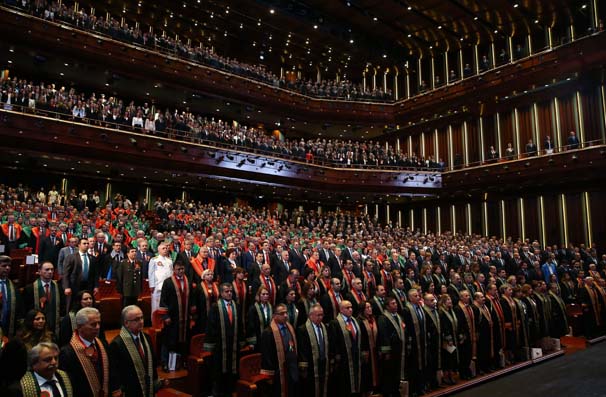

The measures taken on the judiciary is the most striking one, as it involves a large number of the judiciary including senior members of the judiciary. The dismissals and prosecutions also included two (2) members of the Constitutional Court, five (5) present and ten (10) previous members of the High Council as well as fourteen (14) election candidates to the High Council. Around 4.250 judges and prosecutors have been dismissed by the High Council without any individualised procedure and without a right of defence. Nearly 3,000 judges and prosecutors, 170 of which are members of the supreme courts have also been subject to criminal procedure and currently under arrest. The Constitutional Court, the Turkish High Judicial Council, the Court of Cessation and the Council of State put their signature under the dismissal of their members, relying on the emergency decree law without any concrete evidence, any right of defence and any individualisation of alleged actions.[8] The criminal peace judgeships have been the most exploited instruments especially in the resulting high number of arrests and detention orders amidst the failed coup. The most striking example of the types of measures taken by the criminal peace judgeships is the arrest and detention of 2745 judges and prosecutors at one go just within a single day on 16 July 2016 following the attempted coup.

It is not disputed that the criminal peace judgeships were designed, structured, staffed and instructed by the executive specifically in order to rage a war against the persons allegedly linked to the Gulen group which Mr. Erdogan and his government first called the ‘parallel state structure’ after the December 2013 corruption investigations and later as ‘a terror organisation’. The expressed intention behind the creation of criminal peace judgeships, the politically motivated appointment of judges and prosecutors, an appeal system operating as closed circuit allowing reviews only among the judgeships, the image of partiality and working under the executive’s instruction which were also supported by the executive’s public explanations, have all cast clear doubts as to the independence and impartiality of these judgeships, a prerequisite of any “judge or other officer authorised by law to exercise judicial power” (see Article 5-6 of the ECHR).

The criminal peace judgeships basing their orders and decisions on the executive policy documents such as the National Security Policy Document (NSPD) is a flagrant example of the executive’s involvement in the judicial process, thus a sheer example of creating crimes through the executive’s action.

After the attempted coup of July 2016, the extensive scale of crack down coupled with the curtailment of defence and other basic rights not required by the exigencies of the situation have given rise to the fact that the criminal peace judgeships have become an indispensable convenient instrument for the executive under the states of emergency regime continuously applied since mid-July 2016. The criminal peace judgeships have also become a judicial tool with a wider range to crack down all the opposition groups in Turkey including the liberals, the left, the Kurds or whoever considered to be a threat by the ruling regime. The criminal peace judgeships which were specifically created by the executive for its decisive fight against the parallel structure has thus become an important ‘parallel judicial apparatus’ at the hands of the executive against any threats and opposition under the pretext of terror charges.

The public referendum of 16 April 2017 has left the country with a strong presidential system with no checks and balances. A tight control by the president over the judiciary through the newly structured Judicial Council will further deteriorate the checks and balances and the separation of powers to the detriment of the rule of law and independence of the judiciary. The defects and anomalies of the criminal peace judgeships will continue to play the tune of the power holders causing more human suffering and dismay impacting even wider and larger sections of the society.

Sources

[1] For the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), Report on the Functioning of the Democratic Institutions in Turkey, 06 June 2016, Do. No. 14078, paragraph 5 (see https://www.ecoi.net/file_upload/1226_1465286865_document.pdf.

[2] On the objections raised for instance see http://www.radikal.com.tr/yazarlar/omer-sahin/12-eylul-benzetmesi-abartili-olmaz-1177048/ .

[3] For a timeline of the graft investigation and the government response, see http://isdp.eu/content/uploads/publications/2014-muller-turkeys-december-17-process-a-timeline.pdf .

[4] There is ample evidence and consensus that criminal peace judgeships were set up to eliminate the Parallel Structure, see for instance https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vh4TBPAAB-o .

[5] See https://www.amnesty.org/en/countries/europe-and-central-asia/turkey/report-turkey/

[6] See http://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/?pdf=CDL-AD(2017)004-e

[7] See http://www.kararlaryeni.anayasa.gov.tr/Karar/Content/9a5daabd-e182-47c4-a335-f29f272ec46c?excludeGerekce=True&wordsOnly=False

[8] See http://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2016)037-e s. 29-33.

- [OPINION] Right to Defence is Abolished Under The State of Emergency in Turkey - 14/09/2017

- [OPINION] Sad Story of Independence and Objectivity ofthe 16th Penal Chamber of the Court of Cassation - 13/09/2017

- [OPINION] Statement of Judicial Council (HSK) Board of Inspectors Chairman: Investigation Procedure for Judiciary and End of Judicial Independence in Turkey - 29/07/2017