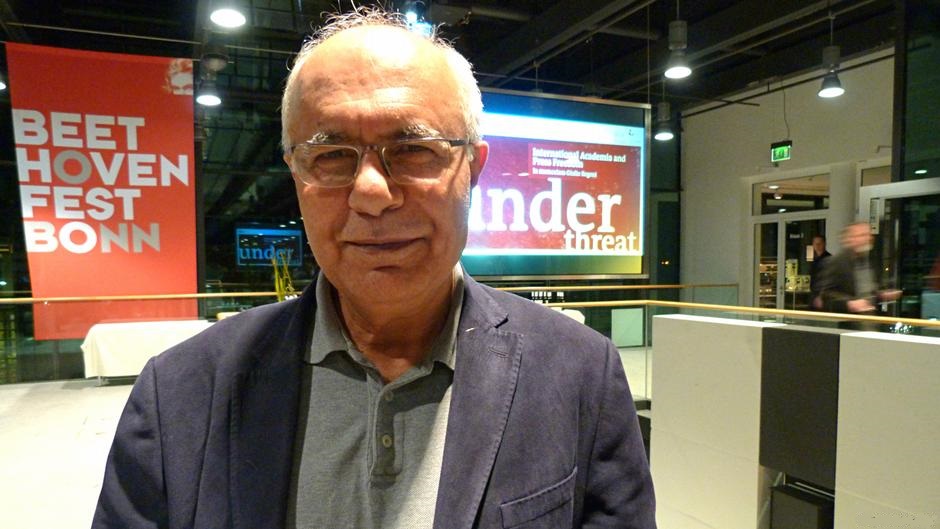

In this article, we interview renowned Turkish author, Çiler Ilhan. In 2011, Ilhan’s book, Exile, won the EU Prize for Literature. She is also a member of the Dutch and Turkish PEN Centres, the voices for literature and freedom of expression in the respective countries. Here, we discuss her work, her personal experiences as a women and the situation of women and girls in Turkey.

The Platform for Peace and Justice focuses on human rights, democracy, peace and justice in Turkey as well as all over the world and thus, it is a great pleasure to be able to talk to you as a Turkish writer about your views and opinions on human rights and women’s rights in Turkey and elsewhere.

In the 1930s, Turkey was a great example regarding women’s rights and even served as a model for the surrounding Middle Eastern countries. Today, however, it appears as if women’s rights in Turkey are declining. Some even argue that women’s rights have been deteriorating since the rise in power of the AKP. Would you agree with this? Are there certain personal experiences that you can refer to as an illustration?

What happened in Turkey in 1930s was just a start. You cannot transform a patriarchal country in a few decades. It needs a solid plan that includes legislation, education of both children and adults and, well, marketing too, if you like. Legislation delivered a big step forward making women firstly “visible”, and then “equal”. Unfortunately, the governments after 1950 did not inherit and continue the mission of the founders of the republic; they fell into populist traps willingly or unwillingly.

Having said this, I truly believe the question of women’s rights is not an issue only in Turkey. There is still a long and bumpy road to be covered for actual equality, even in the most “modern” societies. But in many European countries, the law protects women even if traditions do not; this is the big and crucial difference. And where law is enforced, people have a tendency to follow it on a social level, which then brings a sense of shame to the perpetrators.

We all know that laws can be interpreted, stretched or abused in the hands of the implementers. Hence, under a “big-brother”-esque guise, the government, lawmakers and implementers have started to bend legislation in Turkey… A few days ago, one even said, “laws cannot be higher or more important than traditions.” Now, this is very dangerous. If the law does not protect you, you become vulnerable.

In this sense, these days in Turkey, we are going backwards, not forward. A new, aggressive, backwards culture against women is being carefully seeded; they are putting women back in the kitchen and positioning them as only housewives and mothers in school books, cartoons, state-controlled media and popular culture, in short, through every channel possible. This will also take time to “undo”.

I personally did not go through a certain experience, but it was more a feeling that I got; a feeling of not being protected by the law anymore. I felt unsafe.

Turkey has not only changed since the rise of Erdoğan’s regime, but it has also severely changed since the attempted coup of 2016. Freedom of expression is not as evident as it used to be. Was this difficult for you as a female journalist and writer? How has this affected you and your work?

Personally, I was not doing staunch newspaper or TV journalism, so my field of censorship was more limited than that of in news journalism. But even in our field – lifestyle magazines – we saw changes. We started to be more careful with fashion shoots or other topics that we covered because the profile of our advertisers changed. Our parent company, which also ran a news channel, was subject to a severe censorship that we witnessed daily in the last few years. Some people were not allowed to appear on our screens, some events were not to be covered, or covered only in a way that was allowed. The amount of change was amazing.

Before my last job as the editor of a luxury travel magazine, I managed the PR department of a big hotel in Istanbul for years. We hosted countless press trips and journalists, and in 2012-2013, I remember having a conversation with some Russian journalists. I was surprised to hear how careful they had to be whilst covering news, any type of news. They told us that they were subject to censorship in every field of journalism, and that the state was controlling many things. I remember saying to them, “compared to you, we consider ourselves quite free and lucky”, and I was sincerely upset for them. I could not imagine how they coped with it on a daily basis. Now we can easily compete with Russia.

Turkey was the first country to ratify the ‘Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence’, also known as the Istanbul Convention. At the same time, it seems as if Turkey is lacking the will to implement the Istanbul Convention. For example, a baseline evaluation on Turkey released in 2018 stated that child marriage and domestic violence against women is still a big problem in Turkey. What is your opinion about this situation and why do you think is it so hard for Turkey to combat child marriage and domestic violence?

The problem is that people sitting in “high seats” do not see it as a problem. Therefore, for them, it is not as vital as building mega-airports or roads or compounds or shopping malls. Clearly, it is not a “project”: you cannot make money out of human rights. And, as I mentioned before, this is a whole culture that needs to be transformed. In some parts of Turkey, families marry their children at an early age due to poverty or due to tradition.

They do not see young girls like you and I would see them: for them, they are potential wives and they do not see any harm in this. They would tell you that their mothers also got married when they were 13 or 14 years old. This is just how it goes… You cannot tell these people that the concepts of age and time are different now. Now, humans live longer, and times have changed: girls also have to go to school. If you don’t invest in society, these people are bound to keep believing in the same values for decades.

Concerning domestic violence, I am positive that it is an even bigger issue than it seems because we only read about it or learn something when there is actually a murder or a type of violence that is close to death, and only when incidents are reported at hospitals or police stations. There are so many cases of violence that women do not mention even to their close family and friends; it is just taken for granted. There are various reasons for this: they have nowhere else to go, or they are ashamed to talk about it, or they think it’s the natural, normal way to live life.

A handful of women’s rights foundations must work like detectives to come up with numbers and statistics in order to provide support for these women, the victims. Needless to say, they do not get any help from officials. On the contrary, in many cases they are vilified for supposedly exaggerating or distorting the facts.

I would like to ask you a question about one of your books, more specifically the one that won the EU Prize for Literature. The title of this book is “Exile”, which refers to people that are alienated from their homeland, their families and the community to which they belonged. Do you sometimes feel alienated from your own homeland – Turkey – as a female writer? Why is that?

Exile has reached an international audience because it concerns various levels of humanity and the various conditions of being human. I grew up in a family that was liberal in the sense of education and daily life, but patriarchal when it came to the domestic roles of the genders. I started to think about the issue of being a woman in this society from an early age. I had witnessed how unfair life is for women, not only at home but in many fields.

For example, in business life later on, I worked at big hotels where I saw that women had to work double, and that it actually is a “man’s world”. Again, I must say this was not a “Turkish” issue. I worked at international hotel chains and the macho culture is visible in many European and North American companies. High executives finish deals at bars where women are not invited rather than at morning meetings.

Did I feel alienated as a writer, or as a female writer? No more than the usual level of alienation. Being a writer is not a prestigious occupation in Turkey anyway… Funnily enough, in my professional circle, I used to be better known for my editorship roles and lifestyle journalism for magazines and newspaper weekend supplements more than for my fictional writing. Most of the time, as a writer, you somehow feel alienated. In daily life, I often feel like an “alien”. I don’t feel like talking about the weather, or this or that TV series… I almost always prefer reading, writing or indulging myself in other art forms.

After reading your book, “Exile”, a few stories really stuck with me. Especially the story “My Daughter”, which is about a girl that was the victim of an honour killing by her three brothers. Honour killings primarily affect women and are not only a severe problem in Turkey, but also in many other countries around the globe. How important was it for you to include this story in your book?

This was a true story that I read in a newspaper. I gave it a twist, I gave the characters a voice and turned it into a story. This news literally haunted me. I could not get it out of my head. For me, the real tragedy of this crime lies in the fact that the whole family did it together. Can you imagine? But this must be true for most cases. Not only in honour killings, but in most cases of domestic violence and abuse, including incest.

I see it as a tree with cancer. One branch (usually an adult male) is infected with it first, and then, because a tree is a living organism just like a family, inevitably, the whole tree is infected after a while. And, if one of the branches (or family members) does not want to grow in the same direction as the others, in other words, members who rebel or speak out, they simply cut off that branch.

We must talk about honour killings and incest in Turkey. We cannot pretend that they do not exist. Talking openly will not solve the problem right away, but at least recognising the existence of it, and seeing it as a problem to be solved, would be a start. Even today, we don’t know how many of the “suicides” committed by women are forced suicides or honour killings or another type of domestic violence.

I read that you are a member of the Turkish and Dutch PEN, the international writers’ association that works for oppressed writers, journalists and freedom of expression. Could you tell us a bit more about your work at the Turkish and Dutch PEN? What does the Turkish PEN do to increase freedom of expression in Turkey and how do they decrease censorship?

I am not as actively involved in the Dutch PEN as I am in the Turkish PEN simply because I am not fluent in Dutch – I’m still learning the language. The Turkish PEN is a very active organisation: we have a Women Writers Committee, a Writers in Jail Committee and a Peace Committee (of which I am also a member). These committees are in touch with writers, journalists and academics in jail. They used to visit the detainees but now, for most cases, it’s forbidden to visit. However, they go to their hearings and give them legal support.

PEN Turkey constantly tries to create national and international awareness about the developing situation of freedom of speech, human rights and women’s rights in Turkey through various tools: making, distributing and printing statements, writing in a handful of newspapers that still are able to talk about such issues and using its platform to support NGOs or other groups. For example, this year, the Duygu Asena Award was given to Cumartesi Anneleri (Saturday Mothers) who are searching for their “lost children”.

PEN is also present at various book fairs and events, making its statements concerning freedom of expression and other relevant social and political issues heard. It also organizes its own panels and events in various cities including Samsun, Diyarbakır, İzmir, Bursa, Eskişehir, Ankara and Antalya in this year alone. I represent the Turkish PEN as the Turkish delegate at international PEN conferences whenever I can, updating other national centres on the current situation in Turkey, and continually searching and creating fruitful cooperation between centres.