[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]he repressive turn in Turkey did not begin since the abortive military coup attempt on July 15, 2016. We find the premises in the rhetoric and brutal repression of the Gezi movement in June 2013 and its aftermath.

The coup attempt, however, resulted in an explosion in the number of arrests, dismissals of private and public sector employees and, in the last few months, convictions for “terrorism”. It gave the AKP the excuse and the opportunity to eliminate all its opponents, whether or not they were linked to the conjuration of the summer of 2016.

This repressive episode is not, however, the first one in the history of the country. Without going back very far, we can quote the consequences of the 1971 or even 1980 military coups d’état. This last one led to 650 000 arrests of more or less long duration, often accompanied by mistreatment and tortures, 517 sentences to death (49 of have been applied) without counting several hundred “disappearances”[1] and 30,000 dismissals from the civil service.

These elements and figures are reminiscent of the situation in Turkey since the summer of 2016, and can be used as a comparison with the difference that these two repressive episodes were not led by a civilian government but by military governments against those designated as opponents. How can we characterize this repressive permanence but especially the way it is implemented?

The American historian Charles Tilly developed the concept of repertoire of contentious action to characterize the evolutionary palette of means of action at the disposal of the protesters[2]. This concept, nowadays widely used in the sociology of contentious politics, seems however to be transposable and applied to repression. The idea of a repertory of repressive action allows thinking in the same way repressive continuities and their methods, despite the changes of government and regime.

These repertoires are diverse and depend, in their use, on the political context, the adversaries and the means and skills available to the security forces in charge of the repression. Among these repertoires we can mention individual or collective arrests, kidnappings, disappearances, torture, house arrest, various prohibitions, more or less fair trials, ban/dispersal of demonstrations, etc.

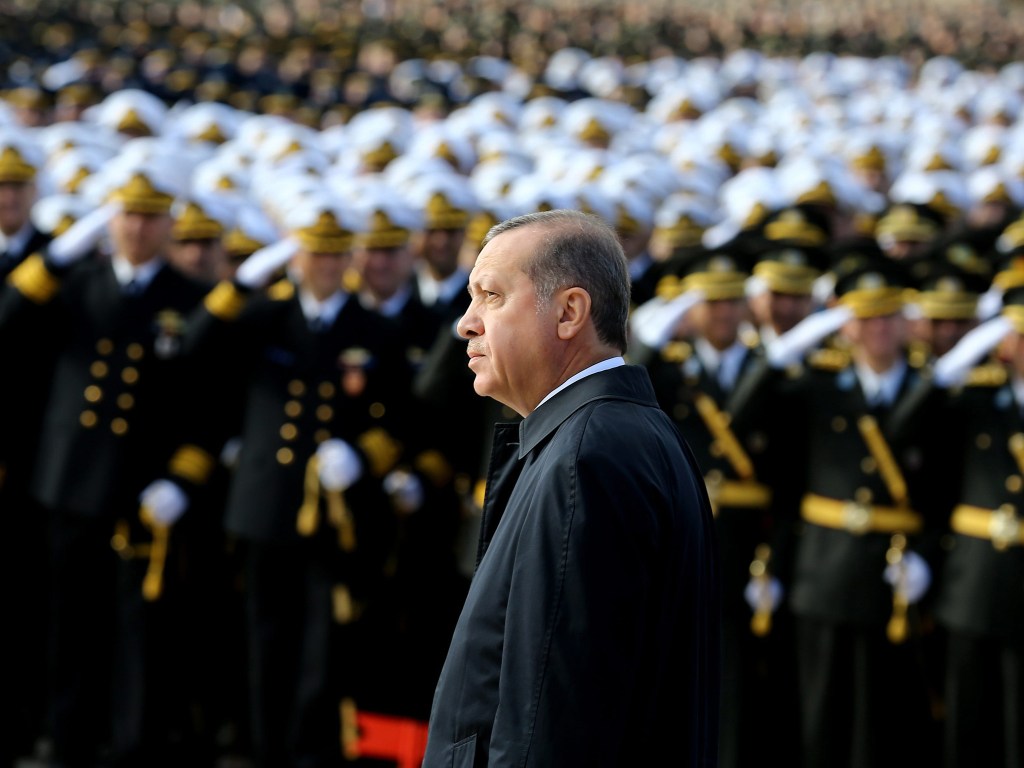

It is also striking to note that repressive repertoires circulate through different periods – from the 1980s to the 2010s to keep going on the example mobilized just before -, through space (we could thus note similarities in the modes of repression between Latin American dictatorships of the 1970s and the Turkish military regime of 1980-1983) but also, and more surprisingly, between actors. One can thus explain repressive gravity in the Turkish context. We would like to emphasize, through two examples, the way in which contemporary Turkish security forces linked to the AKP recycle and turn against a broad spectrum of people, and partly against the military themselves, repressive repertoires that were previously the prerogative of army.

The first example we can give is the long sequence of synchronized mass arrests since July 2016. It is quite striking that the military authorities after 1980, as the AKP authorities after the abortive attempt of military coup d’état, have both targeted and mass arrest opponents (or designated as such) previously identified.

These arrests, sometimes carried out with violence, aimed both to neutralize the actors accused of being responsible for “disorder” or “terrorism” – the left in 1980, the “Gülenists” and progressives in 2016 – and to intimidate on the same occasion any hint of opposition thanks to a very large acceptation of what terrorism is.

Those who have not been imprisoned have been forced into exile to avoid it when their passports were not seized. These “raids” led in both cases to congestion of prison institutions and massive violations of the rights of detainees. Thus, mass arrests and mass arrests methods are mobilized, not necessarily in the same way, but on an equivalent model and with similar objectives.

The second example concerns the way in which justice has been charged with dealing with individuals accused of “terrorism”. After the 1980 coup, the military junta tried tens of thousands of civilians in a collective manner through military tribunals, without the right to defence and without any possible appeal. These trials were spread throughout the 1980s so that many defendants waited several years for their trial in particularly difficult conditions of detention. Under the AKP regime, the resumption of control of the judiciary by the civil power is also worrying.

The independence of justice is now permanently compromised – like many other public institutions – to the benefit of political and exception justice under the antiterrorist law, which remains vague enough to judge many opponents on its basis.

Moreover, another common point with the exceptional justice under the military regime, these trials are conducted with much propaganda and staging outside and in the court. This concerns, of course, the soldiers and officers accused of having participated in the failed coup d’état attempt of 2016, but also all the militants, intellectuals and citizens accused of terrorism without having any connection, either close or distant, to the putschists or any terrorist group.

Many other examples could be mentioned to confirm this idea of circulation of repressive repertoires. This re-appropriation by a civilian government of methods previously used by authoritarian military governments is profoundly worrying for the future and underlines the progressive sliding from a rule of law to a permanent exception regime.

[1] To which must be added more than 1,600,000 judicial instructions, 14,000 disqualifications from Turkish citizenship and the prohibition of thousands of associations.

[2] Tilly C., “Repertoires of Contention in America and Britain”, in Zald M. N., McCarthy J. (eds.), The Dynamics of Social Movements, Cambridge, Winthrop, 1979